Obama made the smart grid a key part of his electoral platform in 2008. Republicans have also supported vast public expenditure on what is quickly turning into a gigantic debacle.

by Cynthia Sue Larson

Like most Americans, I took only moderate notice of President Barack Obama’s announcement on October 27, 2009 of a $3.4 billion commitment to build something called the “smart grid.” My ears perked up when Obama spoke about how the new smart grid would be based on a clean energy economy, and I envisioned renewable energy sources powering every home. I love the idea of clean energy, and I imagined a future in which America’s clean energy leaders would be choosing energy sources and delivery systems that strive and succeed in doing good, or at least in doing no harm, as the word “clean” implies.

“The growth of clean energy can lead to the growth of our economy,” Obama announced, promising that 100 private companies, utilities, manufacturers, cities and others would soon be receiving grants of between $400,000 and $200 million each. This sense of fast forward action suited America’s recessionary times, and resistance was discouraged when Obama called for an “all hands on deck approach,” saying, “The closer we get to this new energy future, the harder the opposition is going to fight. It’s a debate between looking backwards and looking forward, between those who are ready to seize the future and those who are afraid of the future, and we know which side the United States of America has always come down on.”

Few details were explained at this initial presentation. Carol Browner, Assistant to the President for Energy and Climate Change said, “The smart grid is something that has a transformational impact on how energy is delivered. This is about building more than just

miles of wire, it’s about building… something that works.” Having something that works sounded promising, and at the time, I gave the smart grid no further thought.

Canary in the Coal Mine

I didn’t much notice when smart meters were attached to my house, without my awareness or express permission. I didn’t notice that one by one, smart meters were being installed on homes to either side of mine, and all around my neighborhood. I didn’t notice that slowly but surely, my entire city was being outfitted with smart meters… until one day in October I wondered why I awoke each morning feeling dizzy, with nosebleeds, blurred vision, ringing in my ears, and migraine headaches. I wondered why when I was just sitting and watching TV or reading, my heart would often skip a beat, and bizarre muscle tremors would inexplicably spasm muscles on my face, arms, legs, and all over my body as if I’d just been given an invisible electric shock. When I spent ten days away from my home and away from smart meters in Maui, I was amazed at how much better I felt. Gone were all the symptoms which I’d been thinking might have been signs of sudden aging. When I returned home, all the aforementioned symptoms returned, and I wondered what could be causing them. In January 2012, a couple of months later, I caught strep throat and felt sicker than I’d ever been in my life. Unable to feel comfortable anywhere in the house, due to feelings of pain in my head, eyes, ears, heart, and all over my body I slept on the living room floor, and turned my full attention to the question of what, exactly, was making me feel so terribly sick.

When I looked up my symptoms, I was amazed to find that many of them matched what used to be known as “microwave sickness.” The first scientific report of microwave sickness appeared in 1974, with symptoms including: fatigue, headaches, palpitations, insomnia, skin symptoms, impotence and altered blood pressure. In cases of extreme

exposure, symptoms also included: warming sensations, nausea, neuropathy (numbness, tingling, even paralysis in toes and fingers), stomach cramps, dyasthesia (a crushing sensation) and irritability. People in these studies had been accidentally exposed to microwave radiation, and no clear biological markers at that time were found, so these were not the kind of long-term studies that could establish safe exposure levels.

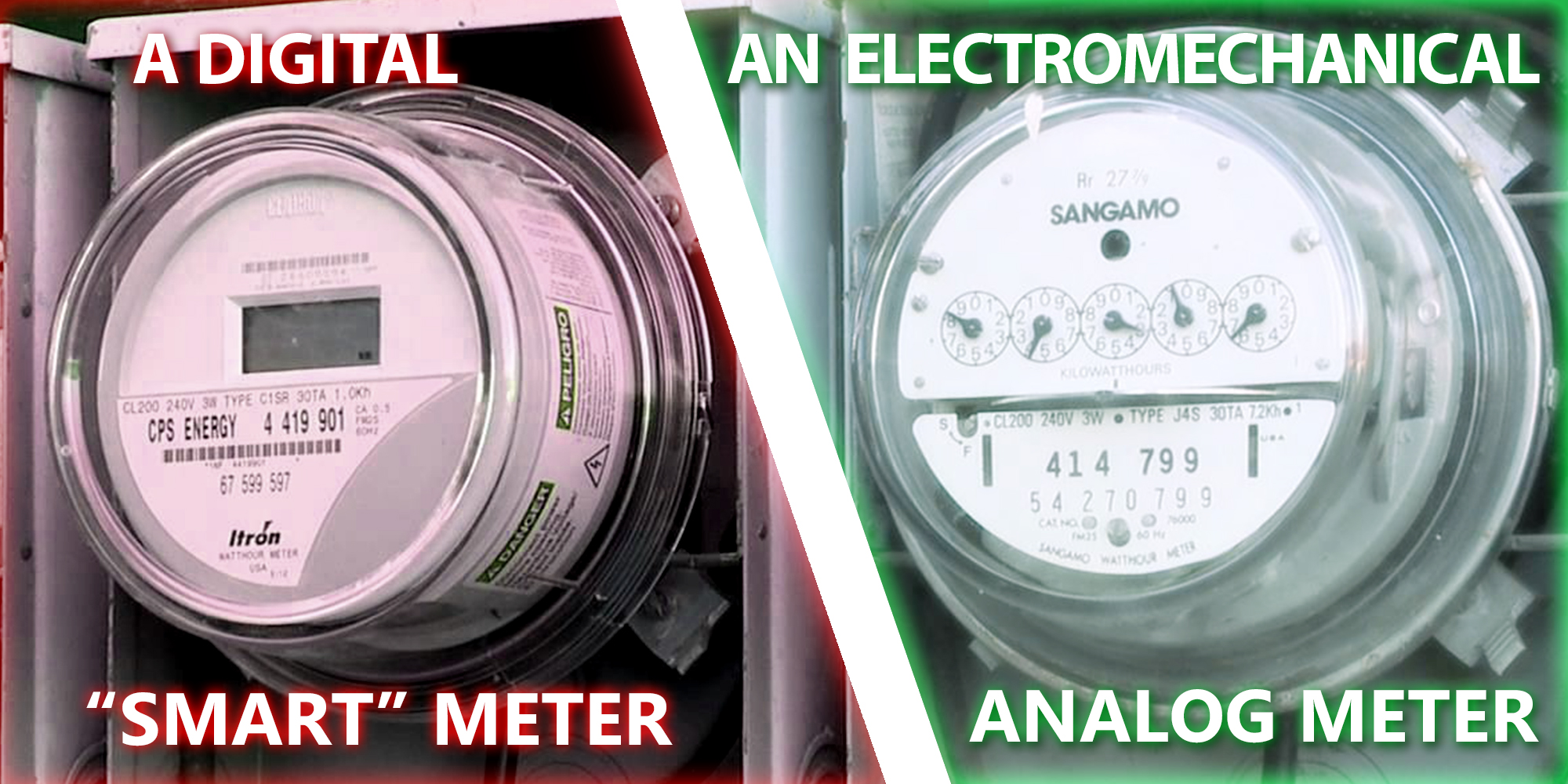

I immediately called and wrote to PG&E, my local utility, asking them to immediately remove and replace the smart meters that were making me so sick on my home with the analog meters I’d had for years, with no problems. The PG&E spokesman I reached on the phone read rather woodenly from some kind of pre-written script, repeating over and over again how “smart meters are harmless.” I explained to him that I have a degree in physics from UC Berkeley, and am well aware that many kinds of radiation that we currently don’t have health standards or studies for are far from harmless, and that I was certain I am experiencing extremely negative effects from smart meters installed on my home. Eventually, this so-called “help” line staffer informed me that there was nothing I could do–there was no way (yet) to opt out.

One of numerous protests at the CPUC against smart meters. Thousands of Californians have officially notified the agency of health symptoms associated with smart meters yet the appointed commissioners refuse to even hold investigative hearings

A few weeks later, I attended and spoke at a public hearing of the California Public Utility Commission (CPUC) in San Francisco. Dozens of people spoke about how they, too, have been adversely affected by smart meters, and I was shocked to hear reports of people who have become so electro hypersensitive that they are living in their cars. On the bright side, I was delighted to hear some good news–beginning in February 2012, California residents in Pacific Gas & Electric’s territories could opt out, for an initial price and an on-going monthly extra charge. This is not a neighborhood opt-out, but rather a house-by-house opt-out, and businesses are not allowed to request to keep the time-tested analog meters at this time.

The Precautionary Principle

With the advent of exponential technological growth in recent years, environmentalists have advocated use of something known as the precautionary principle. The thinking goes that without some kinds of checks and balances, human creativity is bound to occasionally throw caution to the wind, with results we now recognize as being detrimental–regardless how wonderful we originally assumed the benefits of our ingenuity to be.

The idea behind the precautionary principle is that if an action or policy is suspected to risk causing harm to the public or the environment, in the absence of scientific consensus that the action or policy is harmful, the burden of proof that it is not harmful falls on those taking the action. This can be achieved through open communication with the community, who has a right to know complete information about possible known risks and issues. The burden to supply this information lies with the proponent of the new product or technology (not on the general public). Part of this open communication includes an alternatives assessment, with an obligation to examine a full range of alternatives (including doing nothing) before selecting the alternative with the least potential negative impact on human health and the environment. Full cost accounting is part of this assessment, with long-term benefits and costs (including health and environmental impact costs) included. The entire process is: transparent to the public, participatory, and informed with the best available information.

In some legal systems, such as within the European Union, application of the precautionary principle is a statutory requirement. The advantage of the precautionary principle is that it reminds decision makers of their social responsibility to protect the public and the environment from harm whenever scientific investigation has found plausible risk. Only when scientific findings emerge providing solid evidence of no harm shall the wheels of progress roll forward.

It’s Not Too Late

While the city of San Francisco made the news in March 2003 by adopting the San Francisco Precautionary Principle Resolution, and again in June 2005 when San Francisco’s Board of Supervisors passed the Precautionary Purchasing Ordinance… not much of the precautionary principle has yet been seen in action in the United States.

Dr. Gro Harlem Brundtland, former Norwegian Prime Minister, and Director General of the World Health Organization, was injured by a microwave oven and is now sensitive to cell phone radiation.

Many people have stepped forward to acknowledge they have been adversely affected by electromagnetic fields, including some high-profile, well-educated professionals, such as Norway’s former prime minister, Dr. Gro Harlem Brundtland. Increasing numbers of scientists and doctors are speaking up about known and suspected dangers of the pulsed, non-ionizing microwave radiation emitted by smart meters. The World Health Organization (WHO) now lists such electromagnetic radiation as a Class B carcinogen, indicating that it is considered likely to be carcinogenic to humans, and there is increasingly clear evidence that this kind of radiation crosses the brain-blood barrier.

With mounting questions from an increasingly concerned public wishing to know what is being installed in our homes, and interested in knowing what effects wireless smart meters have on ourselves, our children, our friends and our families, it’s time we hold policy makers accountable for ensuring that a democratic, truly transparent decision-making process is taking place with respect to smart meters. The current “Ready-Fire!-Aim” approach to rolling-out wireless smart meters for the smart grid is negatively affecting human health and the environment.

Just as we recognized the proverbial “writing on the wall” with regard to technological wonders of their times: Agent Orange, Asbestos, CFCs, Diethylstilbestrol (DES), Dioxin, DDT, lead paint, and Thalidomide… it’s time for us to stop, wait for results from current scientific studies, do a thorough job gathering all relevant wireless smart meter information, engage in open dialogue all involved communities, and take a careful look at what role we really want wireless smart meters to have in our world today. If smart meters are harming increasing numbers of people, we potentially have a huge ticking time bomb on our hands… one that is leaving few habitable places left on Earth for growing numbers of individuals who have less and less tolerance for modern day electrosmog.

Now is the time for each of us to contact our local government leaders at every level, and ask the simple question, “How can we best ensure that we’re truly moving toward a clean energy future?” When the government and corporations don’t adequately answer this question, it’s up to we the people to make certain this matter is properly addressed.